The Mary Lacy Letters

Davidson College

Slavery and Memory

By Carlina Green & Mary Beth Moore

As diffusers of knowledge, centers of research, and preservers of history, “Universities are unusual in the importance they attach to the past.”1 Universities and colleges, in effect, are museums that preserve memories, and when those memories are traumatic, and “when one insulates the collective conscience—both intellectually and physically—within the confines of university gates,” these institutions of higher education quietly become mausoleums, each “a vessel of memory and mourning.”2 Despite the increasing acknowledgement by some colleges and universities of their involvement in slavery, many others still obscure or deny this particular aspect of their past.

In their book Representations of Slavery: Race and Ideology in Southern Plantation Museums, Jennifer Eichstedt, a sociologist, and Steven Small, a neurobiologist, direct their study of human behavior toward analyzing the ways in which museums, institutions that educate the general public, remember and articulate their histories. They outlined four categories describing how museums provide information about past involvement in slavery: 1. The denial of or lack of admission to any involvement in activities surrounding slavery; 2. The normalization of slavery, often through reference to individual slave owners as institutional founders and leaders without reference to their slave holding and in isolation from the social, political, and economic context enabling the system of slavery in which they participated and from which they profited; 3. A physical separation of information about slavery from the institution’s main outlets for sharing its history, such as a separate tour or webpage; and 4. A full and honest discourse addressing past involvement in slavery. Unfortunately, the latter is the rarest.3 We argue that these categories provide a relevant framework for understanding how colleges and universities memorialize their pasts.

Considering those institutions of learning that have addressed their historical association with slavery, there are more and less successful models. Sociologists Max Clarke and Gary Alan Fine established criteria characterizing a successful institutional response to a history of slavery: 1. Leaders must engage in the “acknowledgment of a wrong committed, including the harm it has caused;” 2. This acknowledgement must be followed up by an “acceptance of responsibility;” 3. Leaders should initiate “an expression of regret and remorse;” and 4. The college or university community should demonstrate a commitment to “non-repetition of the wrong” through educational initiatives, financial reparations, or other ongoing efforts.4

These two lists serve as useful tools through which to consider the responses of other colleges and universities. In 2001, Brown University began addressing their slave-owning and trading past when students and faculty denounced an ad mocking reparations that ran in the school newspaper. In 2003, President Ruth Simmons, Brown’s first female president and the first African American president of an Ivy League school, formed an investigative committee. By 2007, the committee had compiled significant evidence of Brown’s having been founded by a slave trading family and having benefited from slavery in a variety of ways. They published this in a widely distributed report. President Simmons then delivered a statement of apology, created a fund for Providence public schools (which predominantly educate African American youth, many from families with ties to the institution predating emancipation), formed the Center for Justice and Slavery, and established an endowed lecture series on slavery.5 Through these actions, President Simmons and Brown University effectively fulfilled the fourth institutional response described by Eichstedt and Small through creating a dialogue among students, faculty, alumni, and the public. Simmons’ apology and Brown’s subsequent educational initiatives fulfilled all of Clarke and Fine’s criteria.

In contrast, Saint Louis University, a Jesuit institution, has engaged in historical erasure and revision according to SLU professor and historian Nathaniel Millett.6 Although university administrators have not acknowledged this fact, slaves constructed SLU’s early campus “on land once owned in the name of a slave woman,” and once built, slaves worked and lived there.7 Millet hypothesizes that SLU professors and other Jesuit scholars intentionally wrote slavery out of the university’s official history due to their desire to portray SLU as having a “relatively consistent history of pursuing social justice” and because they were ashamed.8 This contradiction was exacerbated during the 2014 student protests following the killings of African American men Vonderrit Myers and Michael Brown in the St. Louis metropolitan area. In their efforts to facilitate reconciliation in the community, the administration emphasized SLU’s historical commitment to racial justice while continuing to ignore their past involvement in slavery and the violent brutalization and dehumanization of African American men and women in entailed. Activists called out the discrepancy.9

Davidson, a predominantly white institution, has branded itself as a liberal island in the middle of a conservative southern state. Similar to SLU, Davidson has committed itself to social justice. We respectfully suggest that we do this through words but not always actions. Some students believe that the institution’s response to recent incidents of police brutality against young African American men and women, including the killing of Eric Scott in Charlotte in fall 2016, only feebly comfort marginalized and threatened members of our community. For example, on Tuesday, April 25, 2017, student protestors posted a sign to our flagpole (a central campus gathering place) stating: “Standing here is NOT ENOUGH when our PEERS’ LIVES are at stake.” We believe that the college should do more to address the underrepresentation of minority, especially African American, students in comparison to the national averages. We note the ongoing lack of designated space for minority students while Patterson Court remains home to predominantly white fraternity and eating houses, a reality we found disturbing when we realized that slaves cooked for and served the exclusively white male students at the earliest eating houses on campus.

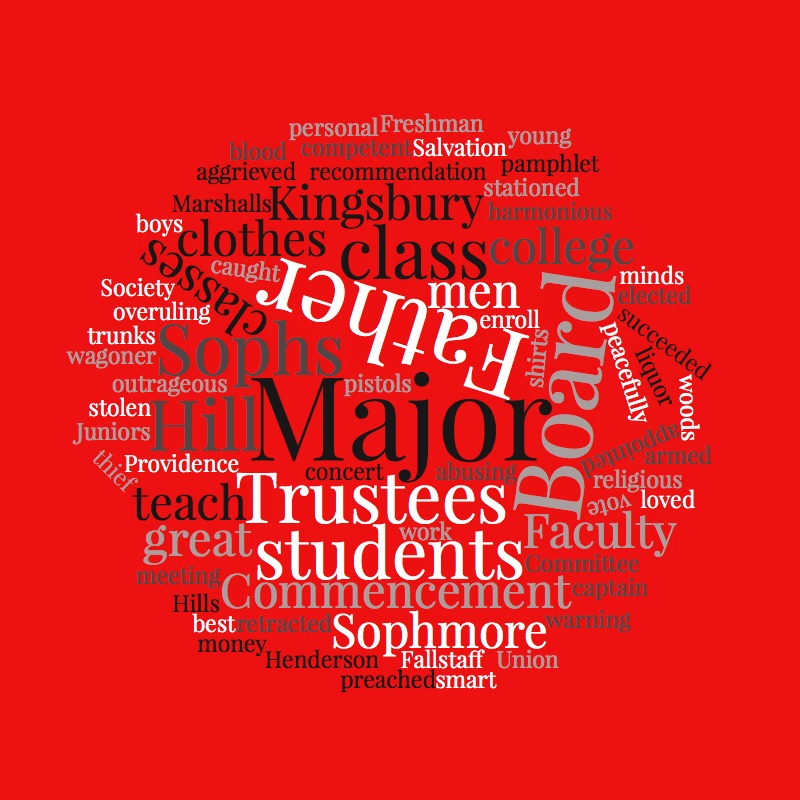

As of spring 2017, Davidson College fits elements of the first category in Eichstedt and Small’s list: exclusion. We were not able to find any official statement (such as on the college’s web page) about past involvement with slavery. Portraits of at least two men affiliated with Davidson College who served in the Confederate Army are displayed in a place of prominence on campus: D.H. Hill and Robert H. Lafferty. The portraits are labeled but no additional information is provided about the men, their contribution to Davidson, or their commitment to the Confederate cause. Although now-retired college archivist Jan Blodgett included information about slavery in her historic tours, student tour guides do not educate prospective or new students about this aspect of our past, new freshman do not learn of it at orientation, and older students generally are not taught about it in classes. Most students simply do not realize that the college was established, built, and run by slave owners, and while the college seems never to have owned slaves, the slaves of faculty and town residents labored for the college and its students.

Davidson’s emphasis on our honor code holds the school itself to a high standard and makes it even more necessary to disclose this information to the Davidson community and the public. To reach the level of open and honest discourse that Brown University has achieved, Davidson must begin the process of researching its slave owning past, apologize, and demonstrate our commitment to preventing exploitation and dehumanization in the future. We believe that Davidson should do this soon. Many of the institutions that have investigated their histories of slavery did so after a troubling inciting incident, but this does not have to be the case. We can lead by example in addressing our past ties with slavery out of our commitment to “recognizing the dignity and worth of every person,” as emphasized in the college’s statement of purpose. Like Clark and Fine, we believe that we can extend that recognition to those who once labored for former Davidson students in a state of bondage in order to create a more just and equitable world for present and future Davidson students.

- Max Clarke and Gary Alan Fine, “‘A’ for Apology: Slavery and the Collegiate Discourses of Remembrance—the Cases of Brown University and the University of Alabama,” History & Memory 22, no. 1 (2010): 86.

- Clarke and Fine, 87.

- Jennifer L. Eichstedt and Stephen Small, Representations of Slavery: Race and Ideology in Southern Plantation Museums (Washington : Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002). See also Susanna Ashton, “Don’t you Mean ‘Slaves,’ Not ‘Servants? Literary and Institutional Texts from an Interdisciplinary Classroom,” College English 69, no. 2 (2006): 156-172.

- Clarke and Fine, 83.

- James T. Campbell, “Confronting the Legacy of Slavery and the Slave Trade: Brown University Investigates Its Painful Past.” UN Chronicle 44.3 (2007), https://unchronicle.un.org/article/confronting-legacy-slavery-and-slave-trade-brown-university-investigates-its-painful-past (accessed April 25, 2017).

- Nathaniel Millett, “The Memory of Slavery at Saint Louis University,” American Nineteenth Century History 16, no. 3 (September 2, 2015): 329–50.

- Millet, 334-38.

- Ibid., 334-35.

- Ibid., 343.